Lost Notes on Afghanistan

Why the West was never really bothered with the plight of the Afghans (despite all “news” to the contrary).

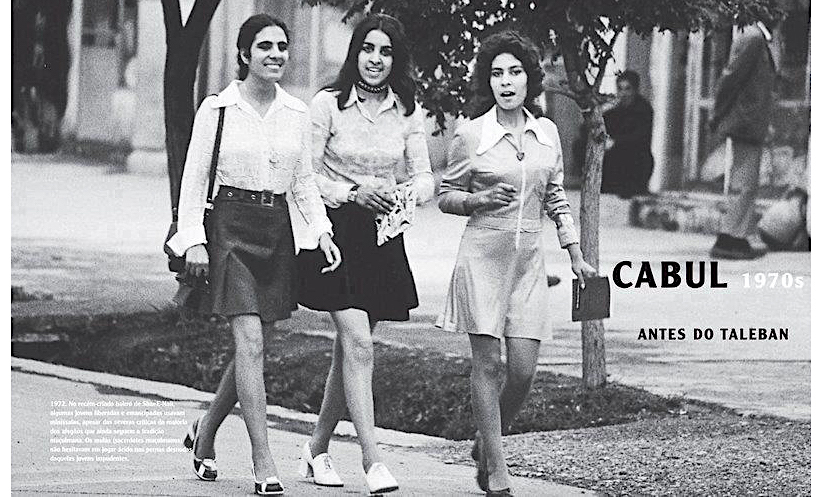

After the fall, at breathtaking pace, of the government of Afghanistan that the West has spent the last two decades propping up, the news space has become littered with tear-shedding for the plight of the Afghan people, particularly women, now that the Taliban are back running the country.1 It has become common place to acknowledge that the West has failed in Afghanistan, and to ask, in a sort of collective introspection, what went wrong. In typical Western hypocrisy, however, the whole exercise is farcical, based on a ginormous lie by omission (which in turn, makes all the current lamentations for the suffering of women, of the utmost cynicism). For the West has failed Afghanistan—in particular its women—but not (just) in the last two decades. It failed them with a foreign policy that can be traced back to, at least, 1979. It is this last part that is always omitted in the West’s pond of tears—and which I now turn to.

One permanent fixture of the narratives conveyed by Western mainstream media, is the fundamental benevolence of Western powers. But the recent history of Afghanistan, offers (yet another) glaring—and tragic—refutation. In 1978, the Islamic monarchy in that country was overthrown in a movement led by the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA)—and thus was born the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan (DRA). In a text very worthwhile reading in its entirety, renown Australian journalist and documentary filmmaker John Pilger recounts what happened next:

The Washington Post reported that “Afghan loyalty to the government [DRA] can scarcely be questioned.” Secular, modernist and, to a considerable degree, socialist, the government declared a program of visionary reforms that included equal rights for women and minorities. Political prisoners were freed and police files publicly burned. […]

For women, the gains had no precedent; by the late 1980s, half the university students were women, and women made up 40 percent of Afghanistan’s doctors, 70 percent of its teachers and 30 percent of its civil servants.2

Given its supposed benevolence, one would assume that the West was thrilled with these changes, right? Alas, no. It would be yet another example, adding to the many history has already handed down to us, that power begets power, and thus cares about nothing other than (more) power. The West’s chieftain nation, the United States—aided by its ever-faithful poodle, the United Kingdom—did reluctantly recognise that the new government did attempt to improve the lot of the general Afghan population, but there was a problem: all that not withstanding, this new administration (the DRA) headed by president Noor Mohammad Taraki and prime-minister Hafizullah Amin, was backed by the Soviet Union (although, as Pilger explains, there is no evidence that the Soviets played any role in the coup that birthed the DRA). And hence, the U.S. concluded that its ‘larger interests’ would be best served by ditching the DRA—even though this would certainly mean a reversal of economic and social progress for the Afghan people. Allow me to translate this into more of a vernacular language: “yes we pay lip service to all that about social progress and justice, but when push comes to shove, that counts for precisely nil. The only thing that counts is our ‘larger interests’—even if the price that Afghans (especially women) end up paying is being thrown back to the middle ages.” How do I know all this? Because of Wikileaks.

In his article that I already mentioned, Pilger refers to and quotes from a diplomatic cable sent from the U.S. embassy in Kabul, which says precisely what I stated above. Pilger never specifically identifies which cable it is, but I think it worthwhile to complement his excellent text with that extra missing bit. And thanks to Wikileaks, I can do just that. The cable in question was sent on Thursday, August 16, 1979, signed by the Deputy Chief of the U.S. Mission in Kabul, Bruce Amstutz.3

One of the reasons the U.S. diplomatic cables that Wikileaks thrust into the open are so valuable, is because they offer candid assessments. This one is no different. It begins by describing the growing—but dispersed and unstructured—opposition to the Taraki-Amin government (i.e. the DRA). This, it continues, is (mostly) due to the public perception that DRA might just be a tad bit too left-wing, meaning that it is perceived by a sizeable swath of the Afghan populace as being a government that is steering away from more conservative Islamic values. This is made plausible by that fact that DRA was backed by the Soviet Union, and the latter had, in fact, banned overt religious practices in other parts of central Asia (e.g., Kazakhstan).

The cable goes on acknowledging that, whatever its faults, the DRA was indeed attempting to improve things in general:

Given Afghanistan’s poverty and backwardness, this revolutionary regime’s goals would probably, in themselves, deserve genuine support from most quarters interested in bettering the lot of the Afghan people.

But in the end, as I said above, the lot of the Afghan people counts for precisely nothing. The lot of the Afghan people, at least as far as the U.S. was concerned, was decided not based on any humanitarian criteria, but by the fact that the DRA had closed ties with “the Russians.” The cable’s final paragraph serves as a searing indictment:

On balance, however, our larger interests, especially given the DRA’s extremely close ties to Moscow, this regime’s almost open hostility to us, and the atmosphere of fear it has created throughout this country, would probably be served by the demise of the Taraki and Amin regime, despite whatever setbacks this might mean for future social and economic reforms within Afghanistan. [my emphasis]

You really cannot put it any more clearly. As for the lot of the Afghan commoner, well, Pilger quotes a female surgeon named Saina Noorani, who offers the following recollection of what happened:

“Every girl could go to high school and university. We could go where we wanted and wear what we liked … We used to go to cafes and the cinema to see the latest Indian films on a Friday … it all started to go wrong when the mujahedin started winning … these were the people the West supported.”4

Afghanistan had a woman—Anahita Ratebzad—as deputy head of state (i.e. Vice-President) during 1980–1986.5 Now, even in their dreams women will likely not reach half as high. Keep this in mind the next time you read a news piece lamenting how the West lost to the Taliban, etc.: the only reason why there ever was a Taliban regime in the first place, is because the U.S. thought it ‘in their larger interest’ to arm a bunch of tribal, backwards and overzealous Islamists (because they would fight the Soviets), rather than work with a progressive, if imperfect, DRA government—basically because they were Soviet-friendly. The Afghan people are—again—paying the price.

September 23, 2021